I don’t consider myself a generous man. I don’t even have the gift of gab, but here I am writing a legacy letter about generosity. The Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research (FAER) has given me an opportunity to share a little bit about my heritage, life experiences, and what motivates me to give. Perhaps you can relate to some of what I share with you in this letter.

For me, generosity grows from my gratitude. I am grateful for my maternal grandmother who left Minsk, Russia, and my paternal grandparents who came from Austria-Hungary at the turn of the century to come to America. They took long and arduous journeys in the holds of crowded steamships across the Atlantic.

I smile whenever I recall my maternal grandmother Shirley Ross. I called her “Nanny.” Distant relatives living in the lower east side of NYC took my grandmother in after she was processed through Ellis Island. She worked as a seamstress, married a dentist, and had two children: my mother and my uncle Stewart. She divorced my maternal grandfather before I was born, so I never met him.

Nanny and I were very close. She invited me to spend a winter with her in Hollywood, Florida, when I was four years old. It is one of my earliest childhood memories. Nanny showed her love through baking. She would bake mandel bread in our kitchen in New Hampshire while visiting each summer. I would love mandel bread even if my last name wasn’t Mandel. Mandel bread is the Jewish version of the Italian biscotti. The dough is shaped into a loaf, baked, and then sliced into oblong cookies. The smell of the almond and cinnamon wafted through her home as did the sound of her laughter and her singing. She also delighted in baking yeast cakes, wrapping them in waxed paper, and storing them in a candy tin. I could eat a million of them.

Her generous spirit was demonstrated beyond the kitchen. For example, until she reached her 80s, Nanny helped “older folks” who had trouble getting around. Without any training as a nurse’s aide, she intuitively knew how to treat the elderly by showing them compassion and respect.

Even though Nanny never had an opportunity to get a formal education, she was well read, had gorgeous handwriting, and wrote beautiful letters. She encouraged me to do what I wanted to do, and what I wanted to do was to go into medicine.

My dad Arnold was another strong influence in my life. The son of a butcher and limousine driver during the Great Depression, he served during WWII in the Army in the Pacific and was to be part of the invasion of Japan had President Truman not dropped the atomic bombs. He went to optometry school on the GI bill and settled with his young family in Manchester, New Hampshire. Alongside my mom Lenora, he raised three sons. (I am the middle one). He taught me that what you do is more important than what you say. He was very involved in the Jewish community of our hometown. He and mom retired to San Diego, California, where he remained active until the end of his life facilitating courses at the San Diego Extension Adult Learning Center and chairing the men’s club at his assisted living facility.

Mom was the glue that held the family together. She and dad met while both were enrolled in Brooklyn College, got engaged during dad’s leave from the Army, and married the year following the end of the war. A traditional wife and nurturing mother of the 1950s and ’60s, she also had a career as a gifted advertising copywriter. Mom always provided me with a safe haven at home even during and after college when I was figuring out what I wanted to do.

I knew from an early age I wanted to be a doctor. My interest in practicing medicine started with my family physician. He took time to listen to me during the examination, giving me 100% of his undivided attention for those few minutes.

I’ve had asthma my whole life, and I really suffered quite a bit when I was a child. I remember going to see the asthma specialist and pediatrician at the Hitchcock Clinic at Dartmouth in Hanover, New Hampshire. At the time, I never would guess that Dartmouth was where I would attend medical school some 13 years later.

I also knew how competitive getting into medical school would be. I started college at the University of New Hampshire. It is a fine school, but it didn’t have a strong reputation for getting students into medical school. I did very well in my first two years there, and then I transferred to the University of California at Berkeley. I worked very hard at Berkeley. As I prepared to graduate, I applied to 16 medical schools, and, although getting placed on one waiting list, I was eventually turned down.

After taking a year off, I thought I might want to do research. I was admitted into a PhD program in experimental pathology at the University of California San Diego, but I soon realized that life in the laboratory was not for me. I really wanted to go to medical school. I reapplied and interviewed again. I got on the waiting list at Dartmouth. That summer I received a letter saying my chances of getting accepted were unlikely. Nonetheless, on the first morning of classes for the Dartmouth Medical School Class of 1979, I received a phone call from the director of admissions. “Someone just dropped out, would you like that position?” asked Director Frances Hall. I went nuts. I withdrew from the graduate program, took the $25 out of my savings account, and caught a direct flight to Boston. I arrived at Dartmouth the next evening. That’s how I started medical school.

After my first year of medical school, I was awarded a U.S. Army Health Professions scholarship. I eventually served 12 years in the Army Medical Department, living in places and doing some things I never would have had a chance to do otherwise. For example, I did my internship and one year of residency at Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii, and I soloed in the TH-55 helicopter as part of my flight surgeon training at Ft. Rucker, Alabama.

I have subsequently enjoyed many rich life experiences, both professional and personal. I eventually settled on the specialty of anesthesiology because it seemed to satisfy my needs for patient contact, procedurally based practice, and intellectual stimulation. As an anesthesiologist, I have had the opportunity to practice in diverse positions in a variety of geographical settings.

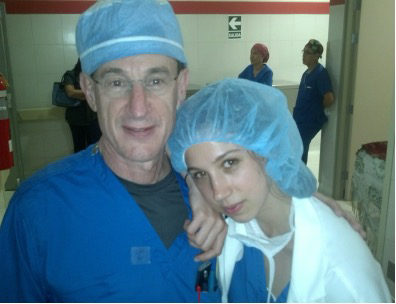

Like my parents, I also try to show by example. I was inspired to go on two surgical missions: the most recent in Peru, under the auspices of Healing of Children. My 23-year-old daughter Rose came with me. She took photographs of children before and after cleft lip and cleft palate surgery, and she also translated Spanish.

We had as many as four cases going simultaneously over five days in three operating rooms at Hospital Regional de Ica, and we had a chance to teach enthusiastic local medical students. Other physicians observed this father-daughter team and were inspired to bring their children on future surgical missions.

I feel very connected with what’s going on in the world and get involved in causes I believe in, such as veterans (our forgotten citizens) and gun control. I see the result of violence on a regular basis while working in a trauma center. On any given weekend or weeknight, we might have to take patients to the operating room as a result of gunshot wounds.

Gun violence has impacted me personally. My friend Ralph Miller became a police officer in Manchester, and at the age of 25, as a new father and with only one year on the job, he responded to a call to deal with a domestic disturbance. Walking up to the house, Ralph was shot in the chest by a 14-year-old who lay in waiting behind a screen door with a high-powered rifle. He died a short time later in a local emergency room.

I made the choice to go into private practice and have been fortunate to provide for three daughters and to set aside some for retirement. It seems appropriate to give some back. One of the ways I have decided to do this is to donate to the Foundation for Anesthesia Education and Research, an organization that does much to improve the knowledge on which our specialty is based. The ability to give my patients the finest care is based on best practices, and these evolve from education and research. In order to keep our specialty vibrant and moving forward, we have to give young investigators the financial resources to do research. There are some great, fertile young minds in anesthesia. They’re the ones that need our help. They can also teach our next generation of anesthesiologists in training programs.

I realize I’m just a cog in a great wheel and my impact on this world is minimal, but I want to make a positive impact. I want my daughters to be happy and productive as well. Like many things in life, I find the more you give the more you get back. What you get back in gratitude and warmth far surpasses your time, money, and efforts. If anything, I’d like to do more. I want to leave a legacy of responsibility and courage of my convictions. I want to be remembered as a guy who tried to do some good in the world and to set a good example for my daughters.

I have worked hard, and I’ve accomplished many of the things I wanted to do. If I were to die tomorrow, I’d be a pretty satisfied guy. How many people never get to do what they want to do? I don’t dream of being a Nobel Prize winner or being chairman of my department. I’m a medical director of an Ambulatory Surgical Center, and I’m happy to do that.

I would like to encourage my colleagues to consider their priorities and to ponder their legacies—what it is you want to be remembered for and how you can be of service to future generations?

Thank you for your interest.

Dr. Alan Mandel

© Pentera, Inc. Planned giving content. All rights reserved.

Disclaimer